«Rough play is a very intimate form of play»

Interview — Sarah Pfäffli

Bilder — Unsplash, Pixabay

«It’s Ok Not To Share» or «It’s Ok To Go Up The Slide» – these titles give it away: In her books, Heather Shumaker questions common educational myths and gives us new and different approaches to parenting – the so-called “Renegade Rules for Kids”. These rules are not simply anti-authoritarian, but also take into account the emotional and cognitive development of children: What can we expect from a 5-year-old? And how can we help him or her in their development? Her approach is constructive and catchy: Her suggestion on how to use pen and paper during a tantrum, for example, to record things that are extremely important to a child is as simple as it is effective. And in many areas she gives parents permission to take it easy – our children won’t be horrible adults because they fight all day or hit other children. They learn. And we can help them.

Heather Shumaker, what’s the difference between rough play and conflict?

Rough play is a game. It’s two people wanting to play together. So if you see your children playing together physically, you need to check and see: Is this fun for both of them? Wrestling can be a fine game. But maybe one child is having a wonderful time and the other one is almost crying and doesn’t like it. So if one child likes it and the other doesn’t, it’s not a game, it’s conflict. On the other hand, conflict does not always have to be physical. Conflict can manifest itself through words or mean faces.

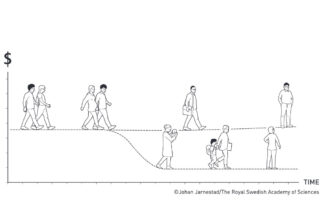

Why is wrestling a fine game? Why is rough play good for children?

I don’t know if you have this word in German, but in English we call it «puppy play». Dogs, monkeys, wolves and cats – all these social and intelligent mammals play this way. It’s very important for the young’s’ social development to engage in this kind of wrestling, rolling around, pretending to hit each other or bite each other. The parents do it with the young and the young do it together. It’s a way for them to bond and a way to figure out their social order. We like to think of humans as intelligent and social animals. And yet we are surprised when our young like this kind of game.

I feel like not all children like rough play.

Not all children are drawn to it. But most will be, if they’re exposed to it and told that it’s ok. Then they will do it, no matter how many times their parents tell them not to. Some children seem to need it more than others.

«If you have a play fight with somebody, you connect on a completely different level than if you just sit at a table together.»

What happens when there is rough play?

It creates friendship bonds between siblings and between friends. If you have a play fight with somebody, you connect on a completely different level than if you just sit at a table together. You start laughing and you get very close, it’s a very intimate form of play. As long as both parties are having fun and there’s no conflict, it’s a pro-social game with a partner, which can create a very strong bond. Once they have bonded, they can do more things together. Maybe their play can get more sophisticated. Getting physical isn’t necessarily mean or violent or criminal. These kids won’t grow up to be horrible people.

What if parents prohibit rough play?

Adults, especially mothers or female teachers, often get nervous about this kind of play. We don’t understand it. And so we want to shut it down. But if we talk to the grown-up men in our lives, whom we love and of whom we know that they are good people, they will often laugh and be comfortable with this kind of play. They will say «Oh, I did that as a child!» Young children, boys in particular, often don’t have advanced verbal skills. This deprives them of their friendship opportunities if they can’t push their friends or roll on the floor with their friends.

We want to teach our children not to hurt anyone. Isn’t it natural that we want to stop them from hitting and pushing?

When we stop this kind of play that is very natural and healthy, we are actually hurting our children. It’s respectful that if a child likes to be pushed that we allow them to be pushed. It’s respectful to teach children: «If she likes this game, it’s okay. If she says no, you must stop.» It’s a different form of respect. In my opinion, we need to teach our children boundaries, limits; and if they cannot stop when another child says «no!», then we need to help them stop. So this is respect. This is radical respect.

So we are supposed to respect that a child wants to play a game we don’t like?

If a child likes a game, we need to let them continue it. However, we need to help children learn how to set boundaries by saying: «I don’t like it when you hit me! I don’t like when you take my shovel!» And a child that has a limit set on them needs to respect that limit. Not necessarily from an adult, but from another child, so it’s peer-to-peer-respect. This is important all the way through life.

«Children will get used to standing up for themselves and setting a limit, but also to hearing it and control themselves.»

How?

Children will get used to standing up for themselves and setting a limit, but also to hearing it and being able to stop those impulses and control themselves. It’s important for adult safety also. When we think about the Me-too-movement we realize that being able to stop people from touching our bodies or doing things we don’t like at any age is essential.

And children learn that when wrestling?

Through a game of wrestling we can learn how to set and respect limits. It’s all about listening to what someone else wants and respecting their boundaries. We care that children develop skills of peace. We don’t want them to fight. But we cannot learn peace just by talking about it. You have to learn it by experiencing conflict. So they need practice. We can’t just sit down and say: «Now we learn about peace.»

Should we as parents make rules for rough play, like no biting?

In general, adults need to set the timing and location rules. The children need to know when and where it is okay to play the game. Maybe they would have to bring out mats or go to another room for that. If the time and place are established, then I think it works best when the children make the rules. But especially in the beginning, when they are getting used to this kind of play, they will need your help to be nearby, because if you have an exciting, high energy type of game, like wrestling or boxing or play fighting, conflicts will usually come fast. It’s all concentrated, because it’s such high energy. So maybe they will want to play a game of hitting each other, but the first hit is too hard and someone starts crying.

That’s when we stop the game?

Maybe they want to continue with the game. So you need to be nearby at least in the beginning to help them sort that out. You could ask them: «Do you want to make any rules?» They will probably say no. When something happened, you can help them understand : «What is it that you didn’t like?» – Your job is to say: «Well, tell him, no pulling hair!» Get them to try to set that rule. That’s all practice for peace skills. I like to write it down with a pen on paper: Rule number one: Jack says no pulling hair! And then they play again – and soon something else comes up, and you help them to write down rule number two. Once they have sorted out these basic rules for themselves, they can usually play for quite a long time.

What’s the point in writing it down?

They are learning the power of their own words even if they can’t write or read yet. Writing the things down that your kid would like to say is a very powerful way to handle many different situations.

«Writing the things down that your kid would like to say is a very powerful way to handle many different situations.»

Let me ask you about weapon play. Our kids love superheroes and toy guns. Their favorite play is reenacting fights. Should we be worried?

Children’s moral development is going to go at a child’s natural pace. How they play is not the same as us making judgements about their play. So it is very, very, very common and natural for children at this age to love superhero play and fights and all of this. It is powerful and kids seek out power. It’s considered epic play where they are trying to figure out good and evil, right and wrong, heroes and bad guys. It’s also a way for them to find out what it feels like to be somebody else, which is a very important step in developing empathy and in moral development. It meets many needs of early childhood, and goes beyond that fact that they are attracted to weapons. They are trying to figure out good and evil and they are trying to fit into this.

But why do they need weapons for that?

According to studies, boys have a greater need for holding an object in their hand when they play than girls do. In order for them to be able to follow their play ideas about their battle or superheroes, they need something in their hands. Imaginary play is very advanced thinking and this helps them make the connections in their brain. They need an object. Girls also use objects, we call them props. A common name is a toy (laughs). Children don’t need toys, but they are helpful during play. And if they don’t have their toy gun, they will use their fingers or a stick.

So there is no point in banning weapons?

When you ban weapons you are telling children “your idea is bad, you are bad”. This won’t take away their interest in weapons but will actually increase it, because you forbid it. So they will take their interest in weapons behind your back. If a young child is very interested in guns and knows that you don’t like them – if they find a real gun, they won’t tell you. This is very scary. Children need to tell you if they think they found a real gun. Their interest in weapons should be in the open.

I still have trouble accepting this very violent play.

Don’t worry if it’s a difficult idea to accept, because we as adults are very scared of weapons, and that’s okay. I have this section in my book on how to become comfortable with weapons play. If you can’t accept toy guns, then accept swords or something else. It is healthier for you and the child if their play ideas are welcomed. And when they do this kind of superhero play, don’t worry so much about how violent the idea is. Maybe they are all dead and blowing things up. What’s important is how they react if somebody gets hurt in real life. If one of your children falls down and gets hurt, do the other children react with sympathy and empathy and go get help? If they show compassion in real life, it doesn’t matter if they kill each other in a game. It matters what happens in real life and how they deal with real life emotions. These games are very complicated. They have a lot of social components. They are always figuring out the rules: «No, I am this guy! You do this!» – It’s very good for the social developement, for reading social cues. It’s very pro social – even though they are killing each other. It’s very much about compromise and negotiations, which are key human skills for peace.

«If children show compassion in real life, it doesn’t matter if they kill each other in a game.»

What if they want me to play along with them? I hate these games. Can I deny them this wish?

Yes. I give you permission (laughs). In all seriousness, it is important for parents to know that they too can set limits. I always invited my mother to have tea parties with me. She hated that game. I would get all my teddy bears with tea cups out. She did not like that game. Once in a while she would play it with me, and then I was so happy. Maybe you can do it once in a while? But it’s okay for parents to say: That’s not a game I like. You could also say: I’m not going to play that game with you, but I will do another activity in the meantime. So maybe you’re in the same room and you do your thing and they are doing their thing. Or you could have what I call «special time» where you spend a little bit of time with each child individually, doing what they would like to do. Maybe it’s only 20 minutes, but they can choose and maybe you do play Lego, as it’s just a short time. It’s about having time where the two of you are together and that helps bond you even more. You may spend most of the day together but since this is a special time, it helps the relationship.

Your children were 3 and 6 when you wrote the book. Now they must be around 12 and 15. Can you now harvest the fruit of bringing up your children the renegade way? What issues come up at these ages?

What I have noticed during the pandemic, is that the skills in this book are what people need – no matter what age. Even as a grandparent, you still have feelings and you will have conflicts. But that’s ok, as long as you know how to approach that conflict and you understand that it’s ok to feel angry and what you can do to speak up and to get your needs met. Of course my children have conflicts, of course I have conflicts – we are human. But the skills a three-year-old learns are important and useful at every age. Many children have told me that they use my book for their college-aged children or for their husbands or wives. Maybe you use different words, but it’s the same idea. Maybe somebody has a conflict, a big feeling, maybe they won’t start biting or hitting – but it’s the same basic idea. I still use those ideas with my children. Some days I’m better at it than others. The ideas are perfect, but we as people are never perfect.

In part 2 of the interview we talk to Heather Shumaker about the difference between rough play and real conflict. And how we can deal with constant fights.

Our thanks go to Stefan Wachs, who helped us with the English version of this interview.

The author has two teenage kids and lives in Michigan. This conversation took place via phone. Her books are available in English and French («Parents, rebellez-vous: Comment résister à la pression sociale et élever des enfants bien dans leur peau»). The audiobook of «It’s Ok Not To Share» is available on Spotify.