Alfie Kohn: «Rewards are just sugarcoated control»

Interview — Sarah Pfäffli

Bild — Eva Hefti

I would love to raise my children with the unconditional approach I learned from your book. However, I find it very hard to implement this approach in my day to day life. Just today I threatened my 4 year old son that we would leave the park if he didn’t stop harassing his brother. It felt like an impulse, a reflex, the first thing that comes to mind in a stressful situation. How can I overcome such an impulse, most likely derived from my own upbringing?

I doubt that I can offer a one-size-fits-all guideline for how each parent can overcome or override the seductive call of the way we were socialized. A critical first step would be to question the necessity and value of an old-fashioned approach to parenting. I can’t help anyone implement a shift from a «doing to» to a «working with» approach to parenting. What I can do is provide evidence for the value of the latter and the harms of the former and offer some broad guidelines for that journey.

What are the harms?

We need to understand that when we punish children we deliberately make them unhappy because we don’t like what they’ve done. This can never get us beyond temporary compliance. And it does so at an enormous cost.

What’s the cost of punishment?

Punishment undermines our relationship with our children, so that they are less likely to trust us. They come to see us as enforcers rather than caring allies. As a result, they are less likely to ask us for help or confess something to us that they are not proud of. Punishment also fills children with rage and defiance and the desire to get even. It teaches them the value of power rather than whatever lesson we had hoped to impart. Above all, punishment puts the focus on the impact of the child’s action to himself rather than the impact on other people.

«All punishment, even when described in euphemistic terms like ‹consequences›, makes a child more egocentric.»

Can you give an example for that?

A punitive consequence leads children to ask the question: What do they want me to do? And what will happen to me if I don’t do it? How we punish, the means we use to punish and how we explain punishment all really don’t matter. All punishment, even when described in euphemistic terms like «consequences», undermines and retards a child’s moral development and makes her more egocentric. These inevitable consequences of punishment are what we have to weigh against the passing guilty satisfaction we get from having shown them who’s the boss.

How come punishment is so common when it has so many negative effects? How can it still be so dominant in parenting?

First of all, not only is punishment accepted in general terms but it is also expected by those around us. Many of us were raised with punishment. We learned about parenting from the way we were parented. And then we see it reinforced by people who surround us. It takes some courage to question this. Furthermore, punishment is popular because it’s easy.

«Punishment is popular because it’s easy.»

Punishment is easy? What do you mean by that?

To work with children to solve problems in a way that’s authentic and respectful and ultimately much more effective takes some time. It takes effort and talent and care and courage. None of these things are required to make children suffer when they have done what we told them not to do. You can sometimes see a short-term effect from punishment. When the threat is severe enough, children will temporarily stop doing what you don’t want them to do. So we conclude that punishment works. However, it isn’t always clear to us that the consistent, multiple, longt-erm negative effects are due to punishment. So we keep doing what we think works in the short run – and therefore we make it worse.

Does this apply to every form of punishment?

Yes. Punishment of any kind, including forcibly isolating children when they need us most – most commonly referred to as a «time out» – has the same detrimental effect.

«Rewards and punishments are not opposites. They are two sides of the same coin.»

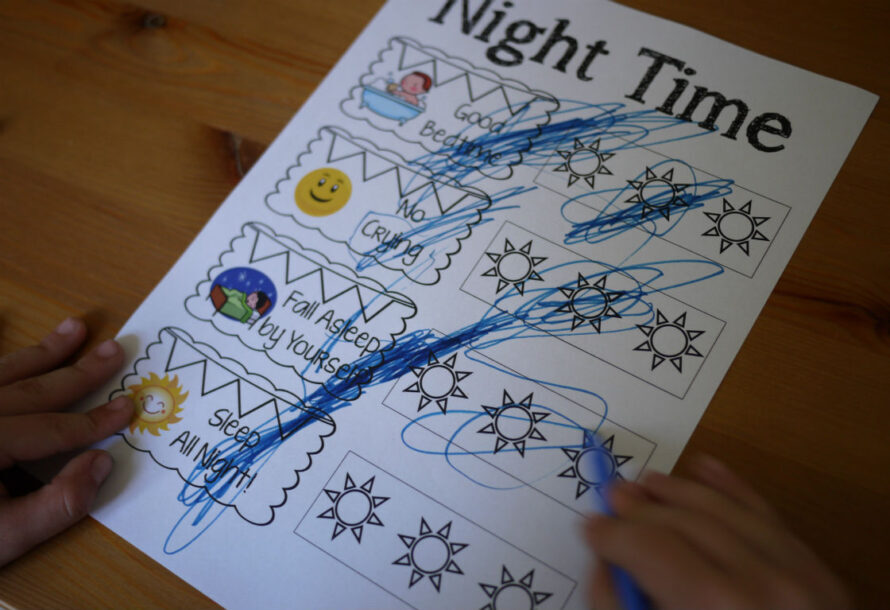

It seems to me that more and more parents understand that physical punishment is harmful. Rewards, sticker systems sweets and praise on the other hand still seem to be accepted. You claim in your book that both approaches harm children.

Rewards and punishments are not opposites. They are two sides of the same coin. In the case of punishments we are saying to children: «Do this, or here is what I am goning to do to you.» In the case of rewards we are saying to them: «Do this, and here’s what you’ll get.» Both are examples of what I’ve called a «doing to» — as opposed to a «working with» — approach. Both are focused only on the behavior at the surface, not addressing the children’s motives and needs and reasons. As a result it doesn’t help children to think about the impact of their behavior on others. If I threaten you with something, it’s obvious I am trying to control you. At the same time, offering a reward or a verbal doggy biscuit as in «Good job! I like the way you … » is just as manipulative. It’s just sugarcoated control.

I hear from friends that the sticker system seem to work with their children.

Research very clearly shows that, as with punishment, rewards can only achieve one thing, which is temporary compliance at an enormous cost. And the cost is often similar to what happens when we use sticks instead of carrots: We make kids more focused on self interest. Studies have shown consistently that children who are often rewarded or praised are more selfish than children who are not. And the effect is most pronounced if they’re rewarded or praised for being generous or helpful. If the person with the power catches me being generous or helpful, I will get something from it. So this child is now less likely to help others when there’s no adult around to offer a reward than he or she was before.

«Studies have shown consistently that children who are often rewarded or praised are more selfish than children who are not.»

What about achievements? Does this apply to learning new skills for example?

Rewards also undermine an interest for doing other things. What matters is not how motivated the child is – but rather how the child is motivated. Psychologists distinguish between intrinsic motivation – which means you do something because you see value in it and it gives you a sense of pleasure – and extrinsic motivation, which means that you’re inclined to do it in order that something unrelated to the tasks will happen, such as getting a reward. The point here is not only that these are two different things, or that intrinsic motivation is better. What matters is that extrinsic motivators tend to undermine intrinsic motivation.

Can you give an example for that?

The more you reward a child for doing something, the less interest the child is likely to have in whatever he or she had to do to get the reward. For instance the best way to destroy a child’s interest in reading is to give the child a prize or praise for reading books.

«The best way to destroy a child’s interest in reading is to give the child a prize or praise for reading books.

Is there any grey area with praise? I find it very hard not to show pleasure when my son achieves something great. It just feels artificial to me not to praise him sometimes. I try hard to be descriptive and not to judge him, but this doesn’t feel very authentic at times.

Let’s be honest : it is our need to say it that we are responding to, not the child’s need to hear it. That should immediately make us wary of the possible consequences. It’s true, however, that not all praise has the same effect. There are gradations here. The most destructive kind of praise is the kind that’s used explicitly to manipulate the child. Where we say: «Good job!» In order to make the child do that thing again. Then it’s purely a matter of control. Not only is it obnoxious but it’s also likely to be counterproductive. If we say something positive about what a child has done with no eye to future effects, but simply because we are feeling excitement about it, then we have cleared the first hurdle, so to speak. However, just because what we said is authentic doesn’t mean it will be innocuous.

Why not?

What matters is how the child experiences our comments. If the child experiences the praise as an extrinsic inducement, a patronizing pat on the head, it’s likely that despite our good intentions the child will be less intrinsically motivated in the future. At the same time the child may feel controlled and less autonomous, having to look to Mom and Dad for a judgement rather than taking pleasure or pride in his or her own accomplishments. That’s a problem, no matter what our intention was. One way of considering the child’s experience is to see whether she comes to us asking for more judgement: «Did you like this?» «Is this a good painting?» «Did you see how generous I was?»

«Praise is not ultimately about encouragement. It’s about judgement.»

Doesn’t every child seek approval?

When a child starts doing that, alarm bells should go off. This is a child in danger of becoming a praise junkie. And that’s not human nature. Rather, it’s a reflection of how the child felt controlled by the verbal rewards we felt compelled to offer. Praise is not ultimately about encouragement. It’s about judgement. It’s evaluation. Sure, children need to know we are there watching. They need to know we care about them. They need guidance from us and help in solving problems. What they don’t need from us is constant evaluation. And a positive judgement isn’t more constructive than a negative judgement.

Really?

In fact one of the things I came around to understanding is that praise is doubly damaging. It’s not just its status as an extrinsic inducement, which reduces intrinsic motivation. It’s also the fact that praise – like time-outs – offers conditional acceptance to children. It tells them that they matter to us, but with strings attached : only when they have pleased us or impressed us. And that is exactly the opposite of what children need in order to flourish. Children don’t merely need to be loved. They need to be loved for who they are rather than for what they have done. They need our hugs and our warmth and our attention and acknowledgement and pride even when they screw up or fall short – in fact, they might need it even more then. So the problem with praise is not just that it’s manipulative but that it’s experienced as a conditional form of affection that leads them to internalize the idea that they are loved, and therefore lovable, only when they fulfill certain conditions. That’s very dangerous.

«The problem with praise is not just that it’s manipulative but that it’s experienced as a conditional form of affection.»

I feel like this is the basis of our society and economy: If we achieve something, we get rewards. It seems like a gigantic task to overcome this thinking in parenting.

Notice the disturbing fact that the way we raise our children precisely mirrors a market-based economy. That’s not a fact of life. It’s a particular economic system that’s based on exchange, that then infects our personal relationships, which come to be seen as quid-pro-quo: You must do this in order to get that. And the last thing I want in my family, which ought to be, emotionally speaking, a safe haven from the cruelty of a market economy, is to recapitulate this economic model of interaction.

So what’s the answer then?

The answer ultimately is similar to what I had said before: We have to become aware of what’s going on. None of this is inevitable. It is our way of treating people that is highly problematic. In the case of rewards and praise it may be possible to move along the continuum from doing-to to working-with one step at a time.

«Kids learn how to make good decisions by making decisions, not by following directions.»

Which would be?

First of all: Give up the punishments. Then give up the tangible rewards. Then give up the verbal rewards. At the same time, though, it’s not just about what we stop doing. It’s also about what we have to learn to start doing. That might include questioning the value of our requests. I discuss this in much more detail in my book «Unconditional parenting». Often when kids don’t do what we tell them, the problem is not with the kids but with what we told them. Secondly, it’s about bringing kids in on making decisions — doing less telling and more asking. Kids learn how to make good decisions by making decisions, not by following directions. Typically, the problem is not the child’s immaturity or unreliability. The problem is with our own deep need to control them. And so we have to begin by challenging ourselves, by looking at where this comes from and facing up to the fact that much of what we are doing may be a function of what we were raised to accept. As the great psychoanalyst Alice Miller pointed out: We may have a desperate need to believe that whatever our parents did to us was done for our own good and out of love. And so we mindlessly reproduce the same destructive forms of parenting with our own children as if to erase any doubt that this was true. It would simply be too terrifying to confront what might be a disturbing reality about the way we were raised and taught.

This sounds so hard. What could help us on this journey?

Talk with other people, other adults! If you are lucky enough to have a co-parent, you can read articles and books on this topic together and discuss these ideas and check in periodically. For example, saying, : «I felt like I was backsliding again, that what came out of my mouth was praise or criticism, I was offering rewards or punishments, I decided unilaterally that our child has to do a certain thing rather than pausing to ask whether it really was necessary or seeing what the child has to say about it. What was your impression?» Parents who have the gumption to question what they’ve always been doing are the ones most likely to parent with unconditional love.

You have children yourself. Did you go through this process as well or did it come naturally to you?

I had to learn too. I didn’t always do it right. I didn’t always have the patience that I should have had when my children were young. All of us are on a journey. But I certainly never ended up using punishment or reward, and that was clearly the right decision.

Our thanks go to Elisa Malinverni and Stefan Wachs for helping us with the translation. Dieser Artikel ist auch auf Deutsch verfügbar (Teil I).

More than 10 years ago, the American landed a bestseller with his groundbreaking book “Unconditional Parenting”. In it he explains in a comprehensible way why punishment and rewards do more harm than good. On his website alfiekohn.org you will find numerous articles, audio and videos. The interview took place on the phone, you can find a German version of the interview here.